A version of this book review appeared in Issue 81 of Cosmos Magazine

Famed for his distinctive narration with hushed tones and restrained awe, David Attenborough is also an accomplished writer, publishing over twenty books since his career began in the 1950s. The books are companion volumes to each series and fine examples of quality science writing, mostly focused on animal behaviour and the evolution of life on earth.

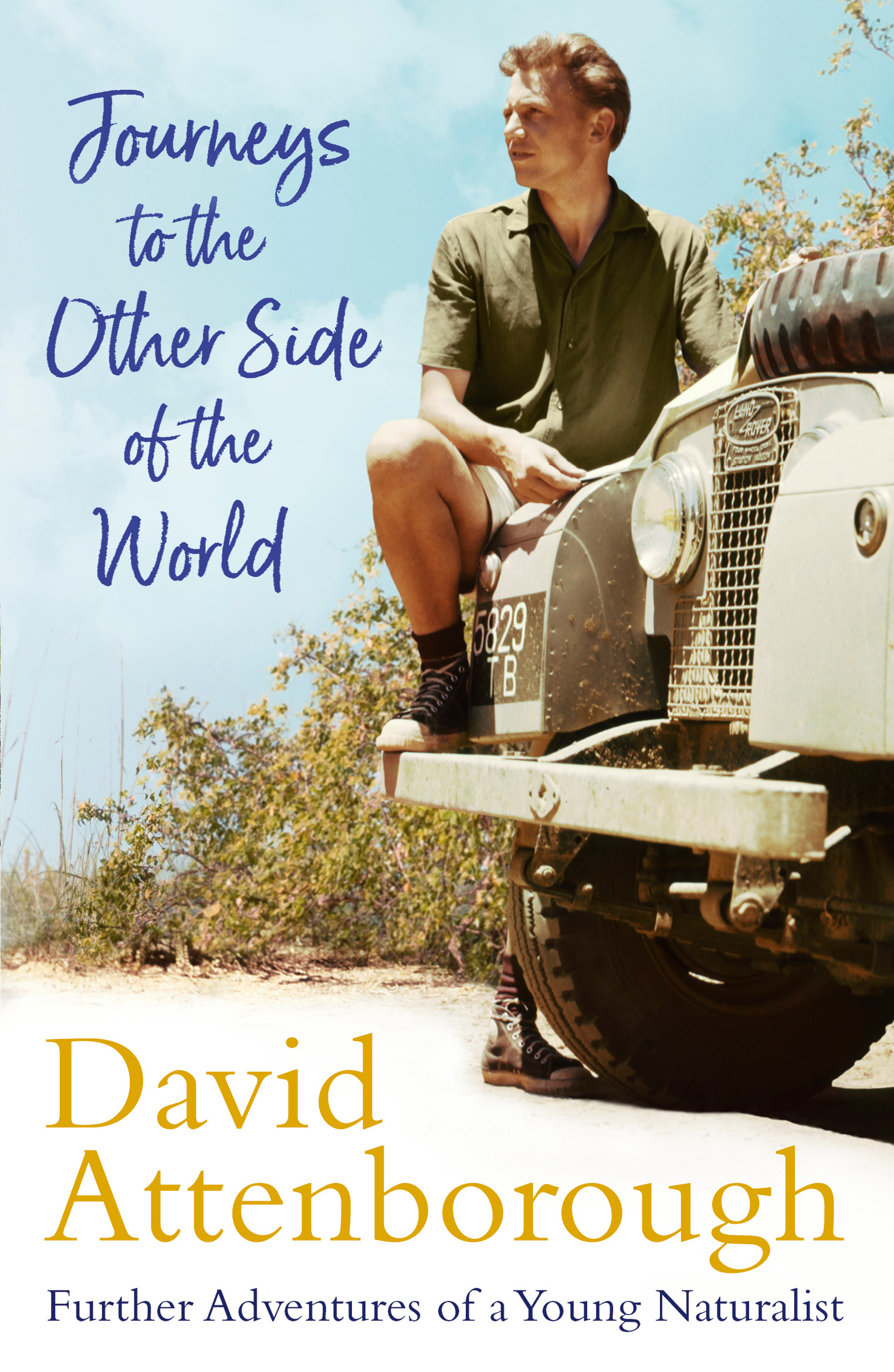

Attenborough spent each year from 1954-1964 going to ‘the tropics’ and making natural history films for the BBC. In 2017, the first three books from these travels were published in a single volume, Adventures of a Young Naturalist. Attenborough’s latest release Journeys to the Other Side of the World; further adventures of a young naturalist comprises the remaining three travelogues.

Adventures of a Young Naturalist contains swashbuckling tales of the capture of wild animals for the London Zoo collection, and filming of exotic creatures in the wild, with encounters with people as somewhat of a side note. Journeys to the other side of the world places the people Attenborough and his cameraman meet front and centre.

And herein lies some of the tension in reading this volume, as Attenborough must necessarily look through the anthropological lens of the times. The modern reader may cringe as Attenborough shares his thoughtful reflections on ‘Stone Age man’, and his interpretation of various cultural practices of the pygmies of New Guinea, the land divers of Pentecost Island, followers of a cargo cult on Tanna Island, or the Aboriginals of northern Australia.

Like many of my generation, I grew up on David Attenborough’s books and films, and adore the man; however he may be a better science communicator than anthropologist!

The first volume, Quest in Paradise is notable as it details Attenborough’s first encounters with birds of paradise, one of his favourite groups of creatures, although it was quite possibly a bittersweet experience. At a particularly large ‘sing-sing’ in New Guinea (now Papua New Guinea), with over 500 dancers, Attenborough estimates that “they must have killed at least ten thousand birds of paradise to adorn themselves for this ceremony”.

Zoo Quest to Madagascar was my favourite of the three books, as it focuses more on the fauna of this remarkable island. Attenborough’s account of the difficulties involved in trying to persuade a determined chameleon off a stick and into a small enclosure is most amusing. The search for the ‘dog-headed man’, a large lemur known as the indri, is a great tale and a testament to how little was known about Madagascan fauna in the West during this period.

The staggering extent of change since the 1960s really hit home for me in the final book Quest under Capricorn, which details Attenborough’s visit to northern Australia. Back then, there was only one paved road. In the entire Northern Territory! The Sturt Highway, affectionately known as ‘the bitumen’.

The colourful descriptions of pub interactions in perfect transcriptions of the vernacular of the time (marauding buffaloes or ‘buffs’ featured heavily) made me fear for a Wake in Fright type situation for Attenborough and his cameraman. Wake in Fright was a horror novel based in the Australian outback and published in 1961. Thankfully, Attenborough’s self-deprecating humour would have served him well and their time passed without incident!

Once the small team depart from Darwin, the book centres upon the rock art and bark paintings and ceremonies of the people of Arnhem Land. Attenborough describes the process of getting to know painters Magani and Jarabili, and knowing something of the reticence some Aboriginal cultures have with sharing culture, I was gratified to read Attenborough repeatedly using the phrase “we did not press that inquiry further”.

Attenborough’s accounts of the challenges posed by filming in the early 1960s may be of interest. Just to capture decent footage of a large goanna took days of planning, as they wished to record both the visual footage and the sound simultaneously. Cameraman Charles had to encase the camera in a canvas padding known as a soft blimp to mask the whirring sound so that Bob could record the sounds of the goanna splashing in the lake; and Bob had to ensure that the various cables enabled later synchronisation of sound and picture. All before the animal took fright and ran off!

Miraculously, using this technique, the small team got their footage and the British public subsequently enjoyed watching an enormous lizard having a swim on the other side of the world.

Nowadays, of course, feature films may be created on a smartphone, and we have had such images like this on our screens for decades, due in the most part to Attenborough’s long and spirited career.

Journeys to the Other Side of the World is recommended for travel writing enthusiasts, and Attenborough fans that enjoy his wry humour and gentlemanly attitude to all those he encounters.

0 Comments